McClure's Magazine and Montessori

by Matt Bronsil, author of English as a Foreign Language in the Montessori Classroom

This magazine holds a unique place in the Montessori world.

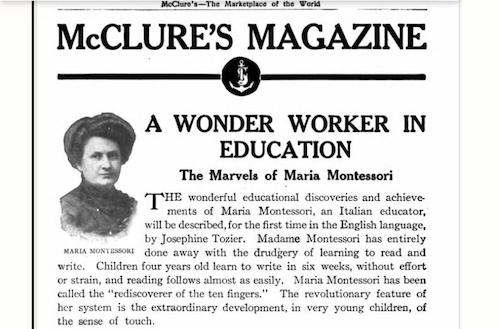

This is McClure's Magazine. It ran from 1893-1921 and had amazing significance in the history of the Montessori movement in America. The Magazine itself used an idea we need more of in today's journalism: writers were given time to study in depth about the subject before putting it out there for print. From 1911 until 1914, McClure's magazine was a driving force in the Montessori movement, largely because of articles like the one above. There had been other articles previous to this, but McClure's Magazine was clearly a driving force in bringing Montessori into the mind of everyday culture, rather than simply the academic world. You can now read these articles on IMonteSomething.com, or maybe you want to just see the historic photos of Maria Montessori and her schools.

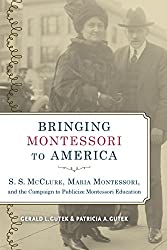

This is a photo of Maria Montessori and S.S. (Samuel Sidney) McClure, the founder of McClure's magazine. To really understand what might have gone wrong with Montessori not spreading in America, we might have to focus on these two people. In 1911, McClure was forced to sell off his role in the magazine when debts became too high and writers left the magazine to work elsewhere (most notably The American Magazine). McClure did end up working out a deal with Montessori where she would come to America to lecture. He also secured rights to use movies of children in her classroom that Montessori created. In the beginning, it looked like they created a perfect match.

Montessori arrived in America in December of 1913, and on December 6, 400 people attended a dinner held for Montessori in the house of Alexander Graham Bell. On December 9, she gave a lecture at Carnegie Hall where they turned away 1000 people. A second lecture was scheduled shortly after. Things were amazing during her first visit.

According to Gerald and Patricia Gutek's excellent book on this subject, McClure had his hands in several different aspects of Montessori and was Montessori's primary American contact for these:

1. The House of Childhood, which is the company set up to manufacture the Montessori materials in America.

2. Montessori's lecture tour in America.

3. S.S. McClure's own lectures on Montessori's method.

4. Ownership and use of films of the Italian Montessori classes.

5. Montessori's American teacher-training courses.

6. The Montessori Educational Association, which was started to help promote Montessori education in America.

To plan for her trip, he acquired the help of lecture agent Lee Kendrick. After returning to Italy, Montessori began expressing huge concerns over her arrangements with McClure. She was particularly upset about the amount of funds she was receiving for her work. The basis of the argument seems to stem from the fact that her costs of the hotels, traveling, and other expenses was deducted from her share rather than on the gross profit of the tour, thus causing her payment to be lower. McClure continued to lecture about Montessori after she left. He used videos of her class in Italy and used these to go on lecture tours, which also caused an issue of McClure not providing Montessori with a copy that she could use. She had also not received money from these lectures, which would have not been a substantial amount anyway. People flocked to see Montessori, not someone talk about Montessori. Things were starting to look bad for the relationship between McClure and Montessori.

When Samuel's youngest brother Robert went to talk to Maria Montessori about bringing her training program to America, she decided to end all agreements with McClure. They offered her 40% of the company that was basically spreading her ideas and methods she had developed. Montessori also wrote to McClure, stating her dissatisfaction with him sending his brother, rather than him coming himself. In a letter to S.S. McClure, she stated her dissatisfaction that he was sending his son to meet with her. (Samuel's son is also named Robert, and Montessori seemed to have a misunderstanding of this point), stating, "But then I became disappointed when you wrote me that your son would have come instead: not because I do not regard him highly enough, but because it was not with him that I began the initial project that had grounded my trust in you personally." Montessori did not welcome Robert welcomingly and saw their business proposal as a way for someone else to profit off her ideas, while she got almost nothing or a small share. Shortly after his visit to Montessori, Robert committed suicide in his home with a gun. (The story is also online): New York Times: R.B. McClure Suicide In His Home. Samuel McClure agreed to give up his legal rights to the Montessori name, and mentioned his regret over anger towards his brother for things going south with the arrangement with Maria Montessori.

We can only speculate at this point, but the disagreements between Montessori and McClure could be the very reason Montessori did not take off in America for a longer period of time. Montessori again returned to America in 1915, but by that time, kindergarten education in America was more set. McClure had a strong influence on the initial spread of Montessori, as well as contacts that might have helped push Montessori into the mainstream.

For more information, read out Gerald and Patricia Gutek's excellent book on this subject.

Matt Bronsil is a trained Montessori teacher and the author of these posts. He can be contacted at MattBronsilMontessori@gmail.com. To subscribe to the email list, visit the Contact Page and you will receive an email when the list is updated.

<<< Back to the article list <<<

>>>View some of the McClure articles on IMonteSomething.com >>>

Recommended Books on Montessori History

Montessori History Blogs

History of Montessori

Maria Montessori

History of Montessori in Taiwan

History

Mario Montessori

Mario Montessori

McClure's Magazine

McClure's Magazine

Montessori Video

Teachers TV: The Montessori Method

Read Old Magazine Articles

Old Montessori Articles

EFL and Montessori

EFL and Montessori