The Montessori Method and the American Kindergarten

by Ellen Yale Stevens

Miss Ellen Yale Stevens, principal of the Brooklyn Heights Seminary , is known to thousands of teachers in this country as one of the most thoughtful , clear-sighted, and experienced American educators. Anything that she may say on the subject of primary education commands immediate attention from the members of her profession, for it bears the stamp of a wise and forceful personality and a deep experience.

Miss Stevens has for years stood at the head of a great school which embraces the kindergarten as a regular feature of its curriculum. Within the last eighteen months, since the beginning of the Montessori movement in this country , the kindergarten method and the Montessori method have been issues in a great controversy which has stirred the whole educational world. The two methods have been constantly compared and contrasted, and each one has been criticized from the point of view of the other. The following article, coming from an educator who has for years studied and observed the kindergarten method in her own school , and who has also made a personal investigation of the Montessori schools in Rome , is one of the most interesting criticisms of the two systems that have been made.

For the first time, I believe, the interest of the whole country has been aroused, the history of educational thought , and not only in the work of Dr. Montessori in Italy, a new movement has come to the present state of education in this front through the medium of a country.

As my first knowledge of Dr. Montessori came through the article by Miss Tozier in the May 1911 issue of this magazine. I am glad to give the readers of McClure’s my own impressions of this remarkable woman, her book, and her theories.

As principal of a school which includes a kindergarten in its curriculum, I have felt for some time that the last word has not been said in primary education, and that problems are arising, conditions have to be met, criticisms must be faced, for which the present system is inadequate. So I gave up more than three months of a busy life to this subject, crossing the ocean in order to meet its founder, to study the methods in its own home, and to compare its results with that of the kindergarten and primary school as they are seen in Rome.

Is the Montessori Material Better than that of Frobel?

I started for Italy with some definite questions in my mind, as, for example: is Montessori a genius? Is her book a real contribution to educational thought? Has her method something in it vital and universal? Has she broken down the wall between the kindergarten and primary classes? Is her material better than that of Frobel, and if so why? Are the children trained by it in useful physical and intelligent habits? Before any attempt is made to summarize the answers found to summarize the answers found to these and other questions, a brief outline of my three months may be of interest.

I sailed for Italy October 2, 1911, on an Italian steamer, and landed in Genoa October 15. I called Dr. Montessori the day after my arrival in Rome, with my letters of introduction. Although she does not speak English, her knowledge of French is perfect. And with this to supplement my Italian, we had a very satisfactory interview.

Meeting with montessori

Dr. Montessori is a woman about forty, fine-looking, with great charm of manner, and remarkable eyes that reveal the student and the psychologist. She greeted me cordially, and arranged for me to meet her two days later at the convent school in the Via Giusti, where her method has been introduced. I was disappointed to find that the lectures she gave the year before would not be repeated, in 1911, as she was busily engaged in the study and experiment necessary to carry her methods into the upper primary classes. In the place of these lectures I at once arranged for two series of private conferences. One series with Signora Galli, the best exponent of Dr. Montessori’s methods, and another with an English lady who had been sent over by influential English people to study the methods with the view of introducing them in English. In addition to these conferences, I have received permission to visit the Montessori schools. In a few days I had all necessary permits to carry out the following schedule:

1) To visit regularly the different types of schools which have adopted the Montessori method.

2) To visit kindergarten and primary classes in municipal schools which have not adopted the methods, I might compare the old and the new methods with the same type of children.

3) To accompany this school-visiting with study and conference with Miss Lidbetter and Signora Galli and, whenever possible, with Dr. Montessori.

This program I followed faithfully for seven wee

In the two schools I visited oftenest, the convent school in the Via Giusti and that of St. Angelo in Pescheria, I was allowed to use the material with the children, and thus became familiar with it, and also was able to follow the progress of the individual children. I saw in this way more than two hundred and fifty children using the Montessori material, and two or three times that number in the ordinary primary and kindergarten classes.

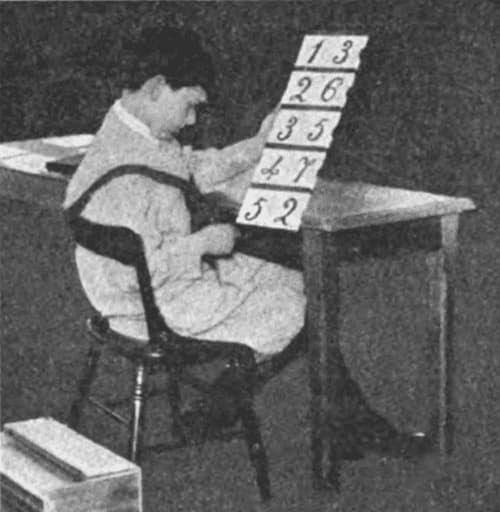

The Italian children of all classes are quick, deft with their hands, gentle, rhythmic, and graceful. But the children in the Montessori schools were far beyond those of their own age in the other schools in self-reliance, power of attention, interest in the work, self-control, coordination, and ability to write, read, and work in numbers.

I was astonished to find so many kindergartens in Rome, but they are without exception of the Frobelian type. The training school for kindergartners is under the direction of a German woman, of about seventy, I judged, with very old-fashioned ideas.

The Montessori Children Far More Advanced than Other Children of Their Age

Why Italian Teachers Prefer the Montessori School to the Kindergarten

A CLASS OF CHILDREN IN THE FIRST AMERICAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL, CONDUCTED BY MISS ANNE GEORGE AT TERRYTOWN, NEW YORK, SHOWING THE CHILDREN AT ONE OF THEIR SINGING GAMES

Several of the teachers I saw in the Montessori schools had taken that course after a longer or shorter experience in kindergarten teaching, and I was greatly interested in their reasons for preferring this method. They all seemed to feel that the approach to truth was more direct, and avoided the symbolism which may appeal to the mature mind, but seldom to that of the very young child. They believed, also, that the material invented by Dr. Montessori was more practical, as it is so simple that the child uses it instinctively in an educational way. They affirmed that by this method individual development was possible to a much greater degree because the natural differences in children and the varying rates of progress always found among children of the same age is provided for; and the strain on the child was lessened when class directions or dictations were avoided and no attempt made to have him follow the thought of the teacher, which is often beyond him. Instead, the child’s self-activity, his auto-education, is greater when he is left more to himself. Dr. Montessori's theory of disciplined liberty, I was told, is as necessary for the children of the well-to-do as it is for those of the poor; the child of the poor must learn to conquer his environment, the child of the rich must learn independence.

Montessori’s Book Unique in the Literature of Education

But, to return to my own impressions of the book, its author, and her method:

Dr. Montessori's “Scientific Pedagogy” is one of the most impressive and illuminating books I have ever read. Considered merely as a human document, it is a wonderful revelation of the simple, devoted, single-hearted consecration of a great soul to a great cause. Considered as a treatise on education, it seems to me to be true to psychology, scientific, consistent, progressive. Combining as it does scientific theory and the history of a personal experience with original didactic material, it is unique.

After reading and studying Dr. Montessori's book, and after several interviews with her, I believe fully in her genius. She has a great personality, and , like Frobel, inspires an intense feeling of loyalty. Hers is a constructive genius, such as was Shakespeare's, so that, coming after a long line of educators, she has unified their theories and added to them from her own powers of intuition and insight.

Montessori a Genius of the First Rank

In her one finds the individualism of Rousseau, without his isolation; the sense-training of Pestalozzi, enriched by most exercises to develop the powers of perception, leading to the apperception of Herbert; Frobel’s belief in self-activity, in the value of play, in the development of instincts and impulses into habits, brought into conformity with modern psychology and child study and freed from symbolism; the patient work of Pinel, Itard, Seguin, with idiots and defectives, enlarged and adapted to normal children. Add to this, long years of study and practice as an anthropologist and a physician in clinics and hospitals; finally, years of testing her theories in an asylum and a social settlement with material of her own invention. Where in the world can you find such a combination of a genius with inheritance, training, and experience? We women should be proud that one of our sex, always considered the teaching sex, has the creative ability and scientific training which enable her to take her place as a real contributor to educational progress.

Just as my study of the book convinced me of its value, and as my interviews with dr. Montessori revealed her to me as a genius of the constructive, inventive, and intuitive order, so my study of the schools of Rome showed me the possible superiority of her method and of the didactic material invented by her over that in present use.

Psychology teaches us that the function of our consciousness is twofold - to bring us into full knowledge of our environment and to bring our environment into harmony with ourselves - and that our nervous system is the means by which this twofold function is performed.

If that is true, education should consist not only in the development of consciousness, so that it may best perform this twofold function, but in the perfecting of our nervous system as its instrument. Such a view of education considers it on a twofold plan, a material or lower, and a spiritual or higher. To the lower plane belongs this perfecting of the nervous system, the developing of inherited impulses, reflexes, and instincts into habits, the coordination of our motor life, and the acquiring technique for the mastery of our environment. On the higher plane we ask of education that it develop our consciousness through the enrichment, first, of our life of sensation, then of perception, then of conception or thinking, and also that it develop the will which is the totality of activity.

If we consider dr. Montessori's theories and her didactic material on both of these planes, we shall find, I think, great possibilities in it for the education of our children. Frobel saw the possibilities latent in the combination of random, impulsive, and reflex acts (the stock in trade of the children) and in the nervous energy which is his birthright; and he devised many gifts, occupations, and games by means of which this inherited and natural capital might be utilized.

Montessori has Gone Deeper that Frobel

But I think Montessori, with a physician’s knowledge of a human being and a teacher's insight into child life, has gone deeper. She shows us how to protect the nervous system from strain, how to follow genetic laws, and how to foster the possibilities of growth. She teaches us how best to give the child mastery of the instruments he needs - the tongue, the hand, the pen - before he attempts much use of them in his thought life; how to help him to become master of himself as a physical being in his daily life at home and in school. She realizes the plasticity of the nervous system and the importance of building into its tissues by developing muscle memory, sensory associations, and habitual reactions.

In the Montessori schools we see children with standards ingrained, as it were, so that they are content to erase and erase until the word or sentence on the slate or blackboard approaches the model in their own minds. I saw such mastery of this technique of writing that pen and ink were used freely by six-year-olds without accident. I saw a child read to herself for half an hour, pronouncing every syllable perfectly, correcting herself when necessary, oblivious of the foreign lady bending over her and the little brother of three playing at her side. I saw children of five or less carrying pitchers of water and tureens of soup without spilling a drop, so perfect was their poise.

All this illustrates what i mean by education on the lower plane, but more important still are the possibilities in this method for education along the higher level, that of the mental and spiritual life.

Accurate perceptions lead to correct concepts. I see the possibilities of proper contents in mathematics, science, and other studies gained by this method. By the approach to reading through writing, this order in the child's growth is preserved. Language is the fullest conceptual expression we have, and reading as a mental act to interpret the thoughts of others is a much higher mental act than writing, which expresses our own thoughts. Then approach to reading by following the steps - coordination of hand and pen, then the muscular memory of letters and words touch, then the application of the technique gained to the expression of the child’s simple percepts, then the recognition of these when written by the teacher in the form of simple commands for him to obey or questions for him to answer - seems to me very logical, just as does the approach to writing, from the geometric insets, through the outlines of these same forms to the outline of letter or word.

Applying the Montessori Method to American Children

A word as to the difficulties we shall meet in bringing this method to the American child in the present conditions of our school life. Here I feel that we have a problem as great as that of Dr. Montessori when she adapted it to the normal child after proving its value with deficients. Temperamentally the American child differs wildly from the Italian: he is less responsive to sense impressions, yet has more imagination; he has a greater fund of nervous energy, with less docility; he has more initiative, more power of invention.

The Italian race is very homogeneous; not so the American. In our blend are found strains of the Norse and the Celt, those northern races with their rich imagination and intuitions. Our children love the mysterious, the unreal, the myth, the fairy story; and this need should be provided for by the story, the song, and the game. I expect our children to be freer with the material - to take some of the steps more quickly and omit others altogether. I hope the excess of nervous energy we find so often in our schools, leading to restless and noisy demonstration, may be more fully utilized than ever before. I also hope that the spontaneous nature of this method, with its greater freedom of choice, its strong appeal to interest, will develop habits of attention and concentration so sadly needed in the later years of school life.

Our conditions here are in some ways less favourable to this method, with shorter hours and long vacations. On the other hand, we have already achieved many things Dr. Montessori is fighting for in Italy. The progressive kindergartens are in sympathy with many of her theories. Most of our teachers are broadminded, well trained, alert, keen, thoughtful. Personally, i should like to see the kindergarten and first primary grade as they now are reconstructed according to her principles, using her materials, but keeping the morning circle and the story, many of the songs and games, and some of the occupations, especially the clay.

The Critics of the Montessori Method

I have listened with much interest to many criticisms of this method since my return from Italy.

Critics see a danger of over-emphasis of the material instead of the spiritual side of education; but I have tried to show how the material is the way of approach only.

Dr. Montessori is an idealist, and implicit in her theories are ideals, reaching out to the home, the city, the nation, to God. There is opportunity for creative work in the use of clay, in free design and drawing, and in the legitimate use of the materials, and especially in composition, of which I saw some remarkable examples in Rome. I gave a little girl of six a flower which I had picked the day before at Tivoli, telling her this as well as I could in Italian. Some time after she brought me, at the teacher’s suggestion, a composition of two pages, in which she told of the Signora American who spoke Italian, of her pleasure in the flower, and gave a little description of it - all this written in ink, without an erasure or a mistake.

Last of all, a word as to the dangers in the method. Much depends upon the teacher - or director, as Dr. Montessori teacher should have a background of culture, knowledge of psychology, power to observe with scientific accuracy, yet with loving insight, the children under her care; she should be able to intervene at the right moment with help or suggestion; she should be able to give simply and clearly the lessons, following the three steps, which have been adapted from Seguin’s method; she should have so clear an idea of what disciplined liberty means that she can create its atmosphere in her room; she should be able to keep the children from superficial playing with the material, and to inculcate respect for it in their minds; she is to prevent desultory habits and foster habits of orderliness. All this is not easy, but it is essential, I think, to success.

While I found poor teachers of this method as well as of the kindergarten in Rome, I also found inspiration in seeing the results obtained by those who understood its principles without being slavish adherents of its method. I speak with enthusiasm, because i believe that from Italy, which has given the world one Renaissance, that of art, comes the Renaissance of education, with a rediscovery and unification of principles already formulated, combined with new theories, methods, and material adapted to democratic society as it is conceived of at the present time. It is our privilege and our duty in democratic America to welcome this new name on the long list of educational reformers, and help by broadminded, thoughtful study of her theories to further the cause of education all over the world.

ANNOUNCEMENT OF A MONTESSORI TRAINING COURSE

McClure’s magazine announces that a four months’ training course for teachers will be given in Rome by Dr. Montessori, beginning January 15, 1913.

Dr. Montessori considers that her personal supervision is of primary importance in the training of teachers. In the course which she offers she will herself prepare teachers to train classes of children according to the Montessori method. The course will consist of lectures on the theory of her method by Dr. Montessori, lessons in practice work, and observation lessons in the Casa dei Bambini.

The lectures will be given in Italian, but will be interpreted by a competent teacher who will answer any questions which may be asked. At the end of the course an examination will be held and diplomas will be given to those who are considered capable of practicing the method.

The tuition for the course will be $250. Board and lodging may be secured in Rome for from six to ten dollars a week. Applicants for admission to this course should make an application promptly to the American Montessori Committee, 443 Forth Avenue, New York, stating fully their education and teaching experience. Further details regarding the training course may be had by applying to the Montessori American Committee at the above address.

Matt Bronsil is the author of these posts. He can be contacted at MattBronsilMontessori@gmail.com

<<< Back to the McClure article list <<<

Recommended McClure/Montessori Books

Montessori History Blogs

History of Montessori

Maria Montessori

History of Montessori in Taiwan

History

Mario Montessori

Mario Montessori

McClure's Magazine

McClure's Magazine

Montessori Video

Teachers TV: The Montessori Method

Read Old Magazine Articles

Old Montessori Articles

EFL and Montessori

EFL and Montessori